To a lot of us Indonesians, Kartini Day is identical to “kebayaan” or dressing up in traditional costumes. This is only natural, because back in primary school, today was the moment our moms went out and about looking for traditional costume rentals to win us our little trophies.

But do we really know who our Mother, Raden Ajeng Kartini is? What made her so famous that a day is dedicated for her? What were the messages that she brought and are they still relevant today?

Raden Ajeng Kartini was born today, 137 years ago in Jepara. Born in the colonial age where class systems were still in place, she was part of the Javanese aristocrat. Being an aristocrat, she had the privilege to attend a Dutch language primary school, unlike the less-privileged children of her time. Sadly, as a girl, she was not as privileged as her male peers in receiving education. It was not the norm for girls to continue their education, and Kartini had to stop hers at the age of 12 when she had to be secluded at home until she got married (in an arranged marriage where she could be the second or third wife of a man she doesn’t know!). With her knowledge of Dutch, she wrote letters to her penpals in the Netherlands about how she wished to have the freedom to learn and receive education, and not just bred and prepared for arranged marriages. These ideas then influenced how native Indonesian women were perceived, and was seen as one of the rise of the women’s emancipation movement in Indonesia.

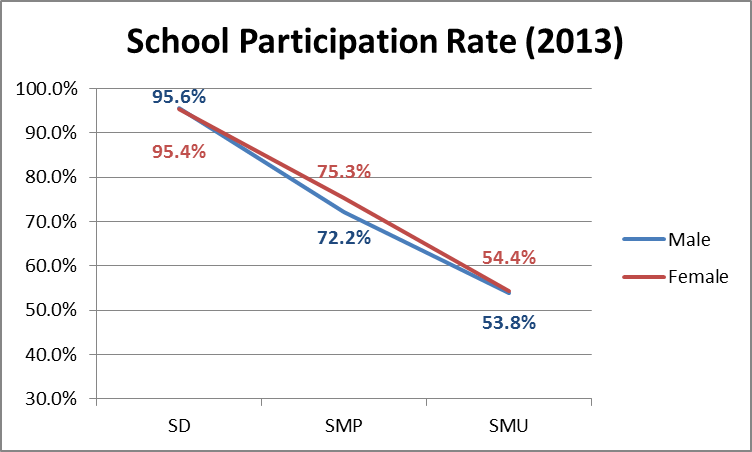

Girls today are much more privileged than the girls of Kartini’s time – I had finished my bachelor’s degree, and in fact, in 2013, Indonesia’s female school participation rate is higher than male1 and there are more female students than male in university2. We can also see girls age 12 and above strolling around the city instead of being secluded at home for arranged marriages. So, case closed, right? We’re already jumping in joy at the finish line, right?

Not so much.

Although we receive better education and opportunities are relatively wider, we are not quite there yet in terms of equal opportunity and equality among genders. The fact is, despite the higher number of school participation rate, there are more men in the workforce than women in Indonesia3. Even more, globally, women do less paid work than men and conversely, spend more time on unpaid work than men do. Out of the 34 coordinating ministers and ministers in the Kabinet Kerja, only eight are women. A 2012 McKinsey report reported that as we go up the corporate ladder, the number of women in the room significantly diminishes, reaching only at 3% serving as CEOs in corporate America. In the US in 2014, women were typically paid just 79% of what men were paid4, meaning that there is a gap of 21% in the pay gap. In Indonesia, the numbers are more encouraging. Based on Qerja’s findings, the average gender pay gap is at 12.36% – women are paid 87.64% of what men were paid (this varies across industries – with utilities & energy having the highest gap, followed by mining, oil & gas).

These gaps – leadership gap, pay gap, unpaid work – and many other gaps are the reality that we are having now. But aren’t girls equally talented to boys? After all, there are more female university graduates than male, right? Are they simply not fit to work? Don’t they have the same opportunity as boys? Do we give the same opportunity to both boys and girls, conscious and unconsciously?

Well, we can trace this back to how we were raised as boys and girls.

As a typical Indonesian girl born in the 90s, as a kid, I played a lot outside – tak benteng, cap jongkok, petak umpet. I also played congklak, and when I grew a little bit older, I started playing with my Barbie dolls and had a mini tin-stove to play cook. When I play with my Barbie gardening set, my twin brother is competitively playing a game of Crash Bandicoot and Tamiya. As I grow older, my male friends spent their recess playing a game of football while us girls watch or stay in our classrooms playing bekel and roleplaying. If you notice, boy’s games have a more hierarchical structure and assignment of roles – there is the captain, vice-captain, goalkeeper, and others. Girl’s games, on the other hand, most often do not. We are accustomed to sharing – we take turns. These habits internalize: I am supposed to wait and share, and thus everyone expects me to do so. It becomes the norm to do such.5

In the professional context, these different set of “rules” and norms between genders lead to a multitude of impact. In a personal case, my habit of waiting and giving way for others led to me sitting on the back seats of a meeting room – not at the table. Interestingly, this is also one of the observations that Sheryl Sandberg made in her book, Lean In: us girls, we don’t sit at the table. In meetings, I personally prefer to wait for other people to finish their sentence, wait for a couple of seconds, before I proceed in giving out my ideas which I phrase in question/asking for confirmation – apparently, learning from a Pat Heim video, I understood that this is not the “rule of the game” in men where men tend to interrupt and have a declamatory voice.Those differences are not wrong, after all, it’s human nature and we are shaped by how the world around us works. However, these unconscious bias could negatively affect how we interact with others, especially those of the opposite gender, as we have different norms and “rules” of the game.

The different expectations put on girls as a child that we internalize – “you have to smile”, “we have to look good and approachable”, “we have to nurture” as opposed to “man up – don’t show emotions!”, “boys have to be strong!”, “alpha male!” – also affect how we see the two genders. An ambitious girl is seen as bossy and is less likeable than an ambitious boy6. Many internet people go to the extent of thinking girls should only make sandwich (whether said jokingly or not), that it’s a highly popular meme. These expectations, norms, and stereotypes then impact how women are treated – and how they treat themselves – in latter stages of their lives, at the workplace, at home, in their communities.

All of this is happening in a world where supposedly we are giving equal, unbiased opportunity and treatment to both genders.

But why do we need a more level playing field between the two genders?

Logically speaking, a fairer world doesn’t hurt anyone. Let’s take a look the impacts if we end the gender pay gap: for businesses, paying workers fairly boosts morale and improves perception towards the company; for the women, well, we get paid what we deserve; and for the men, well, you get paid the same, so no changes for you. Everyone’s happy.

Having more women in leadership position, whether in corporations or in the government, helps. As presented above, we have different set of rules and norms. If the senior positions are dominated by men, who constitute half of the population, only half the population’s concerns and issues are being represented. That’s only half of the potential solutions and answers being brought up. We need different points of view, and having more diversity in the leadership position helps that.

On top of that, a Peterson Institute study shows that going from having no women in leadership positions to a 30% female share is associated with a one-percentage-point increase in net margin.

By looking past gender bias and appraising someone solely based on their own performance, we can have the right person for the job – not the right man for the job, not the right woman. It makes sense both for the employer and the employees. Equal opportunities don’t hurt anyone.

As an individual, what can we do?

First and foremost: recognizing. Recognizing that there are different norms and set of rules. Recognizing that there are indeed unconscious bias and stereotypes in our everyday decision making. Recognizing that there are still, and always will be, room for improvements. By having the awareness, we can step back before we make a decision and assess whether there were nasty biases that came into play.

Secondly, but as importantly, all of us have to participate in this. This is not a zero-sum game; no one wins and no one loses. In order to make it work, we have to work hand in hand: girls and girls, girls and boys, boys and boys.

Unknowingly, us girls can be the most vile commenters to each other – it is very easy for us to dismiss, disregard, and disrespect others. Working moms to stay-at-home moms, those who choose to marry at a young age and those who wait, career-driven women and housewives: we comment and sneer on each other a lot. We made decisions based on our own judgments, we should respect differences. The decisions we made in life, in our career and marriages, don’t make us less of a woman – they shouldn’t make us less of a woman.

And boys are vital in the equation too: making up roughly 50% of the population, even with all girls making it work, we’re still short of half of the population. This is homework for both of us. Kartini wouldn’t have been able to gain as much education as she did and learned Dutch if not for her supportive father. Kartini’s husband allowed her to pursue her aim of creating a school for women. Remember, this is not a zero-sum game.

RA Kartini is celebrated for her ideas that were beyond her time, she challenged the norms. These things that were the norm back then are completely obsolete now. Being a modern-day Kartini is not simply dressing up in beautiful kebaya and matching batik, it is having the spirit to see whether the norms and conditions that we have now have to be challenged and improved.

Looking back a hundred years ago, we would laugh at the fact that girls can only go to school until the age of twelve. Hopefully, in fifty years time, or even sooner, our child and grandchild will look back at us, laugh, and say “funny, back then, they thought girls were not supposed to be leaders”.

Selamat Hari Kartini.

—

Footnotes and references

1Based on Badan Pusat Statistik data, in 2013, School Participation Rate (Angka Partisipasi Murni) in girls at Junior High School and High School level are higher than boys’. The chart below is processed further from BPS data:

2Based on the Ministry of Research, Technology, and Higher Education, there is a total of 2,556,601 active female university students as compared to 2,275,727 active male university students.

3Based on the Ministry of Manpower, the total workforce by gender is 72,150,588 men compared to 42,668,611 women. This can be further diced to different types of workers where most of the work done by men are construction work and farming/fisheries, whilst the only type of work where there is more women than men workforce is professional work, technician, and similar work.

4Based on The American Association of University Women’s The Simple Truth about the Gender Pay Gap Spring 2016. Read their entire report here.

5This fascinating realization came to me from a Pat Heim video during one course I attended on Gender in the Workplace.

6As read in Sheryl Sandberg’s Lean In, Chapter 3, from an experiment by Francis Flynn, then a professor in Columbia Business School and Cameron Anderson, then a professor in New York University, where they tested to students to react to a same successful business case, but with a change of name (a story with Heidi as the character and one with Howard as the character). The students reacted more positively to Howard than Heidi despite the story being completely the same but the name.